Monuments from Soviet-occupied Bucharest

Public monuments are meant to pay homage to special people and historical moments in the life of a nation.

Steliu Lambru, 18.01.2026, 14:00

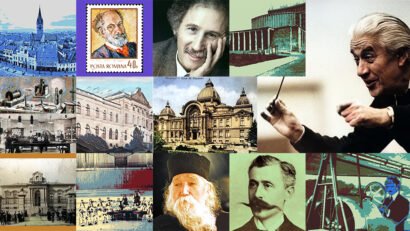

On pedestals, in imposing poses, they have to convey inspiring messages across generations. War heroes and heroines, kings and queens, politicians, cultural figures, religious figures or ordinary people who put themselves in the service of others in moments of crisis are celebrated in this way. Bucharest used to be full of such tributes. However, after 1945, the inventory of these public monuments would undergo a drastic change dictated by the Soviet occupation army and the official ideology of the communist party. Repression and censorship were the means by which the old urban landmarks were replaced with new ones that, through what they conveyed, grossly misrepresented the past and the present.

On December 30, 1947, King Michael I was forced to abdicate and the new communist regime began transforming Romania from a democracy into a dictatorship. The statues of kings Carol I, whose name is linked to the foundation of the modern Romanian state, and Ferdinand I, under whose reign Greater Romania was achieved in 1918, were taken down from their pedestals and destroyed. The same fate befell the statues of leading politicians such as Ion C. Brătianu in University Square, Ion I. C. Brătianu on Dacia Boulevard and Lascăr Catargiu on the boulevard that bore his name. The list of demolitions also includes the Modura Fountain in Herăstrău Park, the Infantry Monument, and the Monument to the Heroes of the Teachers’ Corps. Historian and collector Cezar-Petre Buiumaci is the author of a book entitled “Journey through the Bucharest of Yesteryear”, a visual history of the transformation of the city and its monuments. Buiumaci believes that two practices can be identified in relation to the replacement of public monuments in Bucharest”

“Two elements are at play here. On the one hand, the demolition of monuments that reminded of the monarchy and the main adversaries of the communist regime, great statesmen like Ion Brătianu, Ionel Brătianu, Take Ionescu and Eugeniu Carada etc, including Bucharest’s most important mayor, Pache Protopopescu, although he lived and worked before the communist movement existed in Romania, at the end of the 19th century. His statue was also taken down. More recently, the city hall will launch a competition to recreate that statue. The statues of the kings Carol I and Ferdinand I were also pulled down.”

The demolition of old monuments was not enough. To increase the propaganda impact, the regime erected new monuments, some of which explicitly paid homage to the Soviet Union, while others were more subtle ideologically. Such examples include monuments to the founders of Marxism-Leninism, others glorifying workers’ strikes, moments of class struggle, and monuments dedicated to the army. Historian Cezar-Petre Buiumaci explains:

“On the other hand, new monuments were built. Basically, the first monuments to appear are the occupation monuments: the monument of the Red Army, the monument of Stalin, the monument of Lenin and then of some personalities of the Russian-Soviet culture and the cultures of the other states that fell behind the Iron Curtain after the Second World War, exponents of the so-called proletcultist tendency, therefore of leftist orientation. Then, monuments appear such as the Monument of the Heroes of the Fatherland, which is, basically, a declaration of the communist regime in Romania that Romania had also participated in the Second World War, with great efforts and sacrifices, although Romania had not been recognised as a co-belligerent. The monument becomes the main site where flowers were laid as part of homage paying festivities, even more so than at the monument to the Soviet soldier.”

The construction of new monuments was done mainly in the late 1940s and in the 1950s and 1960s. Historian Cezar-Petre Buiumaci says that the demolition of old monuments was more propaganda-effective than the construction of new ones: “There were fewer public monuments erected during the communist regime than were demolished by this regime. The new monuments were built, mainly, in the early days of the regime. In the later years, there are fewer monuments and they no longer have this deeply propaganda nature but rather cover a need to decorate the city and the parks, the latter being the main sites for the placement of public monuments. Some of these structures are even depicted in postcards and my book has an entire chapter entitled Monuments of the New Regime.”

Naturally, the return to democracy also meant repairing what had been damaged during the years of socialism. The old monuments were put back in their places, and where this was no longer possible, reconstructions were carried out. The socialist monuments were removed by the same methods used to put them in place.