The Romanian journey of French artist Dieudonné Auguste Lancelot

French lithographer, engraver and illustrator Dieudonné Auguste Lancelot was one of the foreigners who visited the Principality of Wallachia in the 19th century.

Steliu Lambru, 30.08.2025, 14:00

French lithographer, engraver and illustrator Dieudonné Auguste Lancelot was one of the foreigners who visited the Principality of Wallachia shortly after the Union of 1859. Born on February 2, 1823 in Sézanne, in northern France, Lancelot specialized in the reproduction of images. The lithographs and engravings he created were used by various French travel publications from the mid 19th century, such as Le Tour du monde, Le Magasin pittoresque, Le Monde illustré, Les Jardins, Guides-Itinéraire and Guides-Cicerone du Paris illustré, guide itinéraire pour les voyageurs. Lancelot’s name is of great importance for the history of the Romanian Principalities due to the journey he undertook in 1860 to what is now southern Romania.

Throught time, political expansion went hand in hand with knowledge and exploration of new territories. In the 19th century, the Romanian world was discovered by Western Europe as the end point of the continental journey of the river Danube. The place where the Danube flows into the sea aroused the curiosity of Europeans. Mihaela Varga is a historian and art critic and she has studied the contribution of foreign travelers to disseminate information, as well as to political decision-making:

“It was customary for a writer traveling to a new place to be accompanied by a draftsman who would make sketches on the spot, just like in the 20th century an art historian or a historian would be accompanied by a photographer. Engravings would then be made from the sketches and published first in a newspaper and then in the form of a volume. Paris was in 1869 the true cultural capital of the world. It was therefore home not only to many historians, many writers, but also to countless professionals from the world of book printing and the production of culture.”

Dieudonné Auguste Lancelot was 37 years old when he arrived in Wallachia travelling on the Danube. He sailed on the river to the port of Giurgiu, 60 kilometres south of the capital Bucharest. From there, he travelled northwest and followed an itinerary that led him to the monasteries in northern Oltenia. And from there he reached the Danube again, westwards, and returned to his homeland. What does a viewer today see through the eyes of Lancelot, captured in his engravings, and what is lost? Mihaela Varga tells us more:

“The documentary value of the objects left behind is very important because, for example, it can be seen that there were some buildings in front of the cathedral at Curtea de Argeș. You can also see the buildings near the Stavropoleos church in Bucharest at that time. There were other delightful details such as villages with houses with very high rooftops that were usually made of straw or reed. The roofs require a very sharp slope so that the water left by snow and rain can drain as quickly as possible.”

Speaking about Lancelot’s legacy in the Romanian world, art historian Simona Drăgan believes that the engravings from Wallachia have a great documentary value, even more so than artistic:

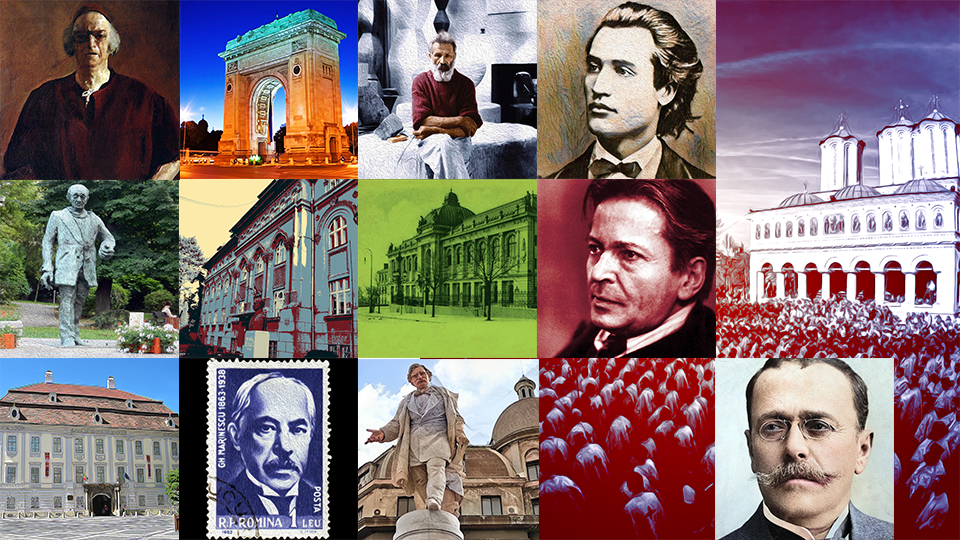

“The 19th century Romanian world is illustrated in engravings made by predominantly French and Central European artists. As art and civilisation historians and philologists, we are equally interested in what those foreign artists saw when they travelled to the Romanian lands, then Romania, in the 19th century. It was a century of accelerated changes that in effect began with the Phanariots and leaves us with a kind of Romanian art nouveau, the art of the 1900s, so a century in which many things happened. Documents, whether engravings, prints and photographs, can be subjected to comparative studies and can provide us with information about the past. The period that art historian Adrian-Silvan Ionescu considers of interest to the West for the Romanian world is that between the Crimean War and the 1877 War of Independence, with consequences that extended to around 1900. Somewhere around 1900, the West’s interest in what was happening in Romania faded.”

Simona Drăgan says Dieudonné Auguste Lancelot’s image capture everyday Romanian life.

“Beyond the representative architectural styles, we have what I call the ‘dead time’ of travelling. Artists travelling to the Romanian countries provide us with images of travelling carriages, boats, and the human typologies which Lancelot saw during his Danube journey. There are many things that we, as art historians, look at carefully. The images read like a book.”