Romania’s Balkan policy after World War Two

It was only after Stalins death in 1953 that Romania started its own initiatives in the region.

Steliu Lambru, 24.08.2015, 14:20

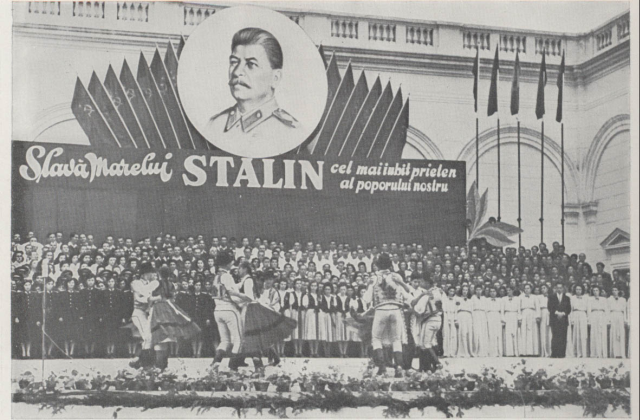

Before 1940, Romania’s policy in the Balkans had been mainly focusing on cooperation and making alliances with various state entities. After World War 2, until the mid-1950s, Romania’s policy in the Balkans was controlled by the USSR and it was only after Stalin’s death in 1953 that Romania started its own initiatives in the region. The country tried to reach out beyond the barriers imposed by the post-war delineation in the Balkans, where Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Albania where under the communist grip, while Turkey and Greece had democratic regimes.

Attempting to improve its international image, in the aftermath of its intervention against the anti-communist revolution in Hungary in 1956, the Soviet Union eased its grip granting some freedom to its satellite countries. In Romania’s case the Soviets took this process a step further by pulling their troops out of this territory in 1958. Romania wanted to make the most of this freedom and tried an economical and cultural rapprochement with its neighbours.

In an interview with the Oral History Department, Valentin Lipatti, a former ambassador, essay-writer and translator, spoke about the initiative of denuclearizing the Balkans at that time.

Valentin Lipatti: “Romania’s first major initiative after the war was Prime Minister Chivu Stoica’s 1957 proposal to denuclearize the Balkans. It was a major, daring initiative, which of course, slammed against a wall of rejection. Whereas Bulgaria and Yugoslavia were largely in favour of denuclearization or turning the Balkans into a region free of atomic bombs, NATO members Greece and Turkey stood against it, and the initiative, no matter how inspired, failed. It wasn’t completely buried, but kept dormant for a year or two. However, this idea of denuclearizing the Balkans got momentum and snowballed into a movement that eventually comprised other parts of the globe.”

With the barrier between communism and democracy seemingly impossible to overcome, cultural cooperation proved to be the only way to cross it.

Valentin Lipatti: “Concurrently with this governmental initiative, which proved difficult because it involved the military sector, and military issues were always the most prickly, a major cooperation process commenced in the Balkans, in the cultural field, consisting in exchanges in education, sciences and culture. But that was at non-governmental level only. And this kind of multilateral cooperation went on for years at this level, which was easier to accomplish and had only few obstacles. This is how a number of associations and organisations operated, such as the Balkan Medical Union, which had been founded between the two wars, the Balkan Union of Mathematicians as well as the younger International Association of South-eastern European Studies, set up in 1963. These professional associations and organisations maintained a sense of trust and cooperation in scientific areas and professional environments in the Balkans.”

The Balkan Cooperation Committee, headed by Mihail Ghelmegeanu, was designed to coordinate cultural activities. However, its success was limited.

Valentin Lipatti: “The Balkan Cooperation Committee, headed by Mihail Ghelmegeanu, was a non-governmental committee lobbying for peace. Such organisations were very much in fashion at that time. There was this idea, mainly coming from the Soviet Union, of holding world-level peace conferences, regional conferences for peace, against imperialism, and so on. In the Balkans, this Committee was set up, focusing on defending peace in the Balkans. It was a multilateral committee, but it did not have a large-scale activity. More important were those professional associations, of medical doctors, architects, archaeologists, geologists, scientists, historians, writers. Their efficiency was twofold. First, a specific cooperation project was established in a given profession, in the field of history, let’s say, or in the field of language studies, or in archaeology. It resulted in research studies, research activities, reviews, colloquia, a multilateral professional activity between the Balkan countries, between specialists from Balkan states. Thanks to this kind of cooperation, these professional circles maintained a climate of good neighbourhood, reliability, friendship and trust.”

However, at a 1976 governmental meeting in Athens, focusing on economic and technical cooperation, the flaws of that kind of policy came to light.

Valentin Lipatti: “The objective Romania was firmly pursuing, just like Yugoslavia, Turkey, and to a certain extent Greece, was to create some kind of follow-up. That is, to create an institutional framework, because one conference, a one-off event, good as it may be, doesn’t amount to much, people forget it. And in this respect, we had to face Bulgaria’s staunch opposition. Our Bulgarian friends claimed they had not been authorised to approve anything like this. Generally, a five-way consensus was quite easy to get. But it was enough for a country to veto, and the decision could not be approved. Bulgaria was voicing the Soviet Unions’ view, and at that time Moscow did not favour economic cooperation in the Balkans, which in time could get out of its control. It saw a common Balkan regional market as a threat, because Romania and Bulgaria were socialist countries, but Turkey, Greece, non-aligned Yugoslavia could take that cooperation to a direction the Soviet Union did not want it to go. So the Bulgarians were instructed to veto the follow-up. That blow below the belt dealt by the Bulgarians blocked the multilateral process for long, for quite a few years, actually.”

The success of Romania’s policy in the Balkans during the communist years was limited. The clashing interests within the same bloc, as well as the different political regimes, were reasons enough to hinder Balkan regional cooperation.