Recent Top Quality Books

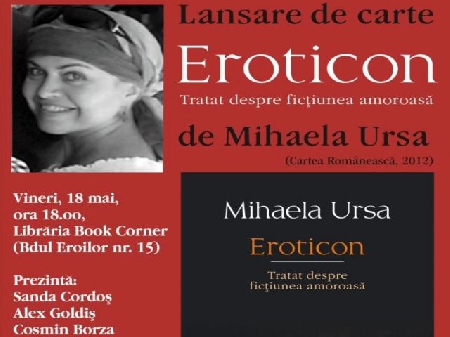

Nora Iugas “Sky Market. A Kitchen Diary and Mihaela Ursas “Eroticon. A treatise on erotic fiction are two of last years most interesting releases. Todays World of Culture invites you to leaf trough those two books.

Corina Sabău, 18.05.2013, 18:01

Mihaela Ursa is the author of “The 1980s in Literature and the Promises of Postmodernism” (published by Paralela 45 in 1999) “Gheorghe Craciun — a Monograph” (brought out by Aula Publishers in 2000) and “Writing-topia” (released by Dacia Publishers in 2005). The books were awarded prizes by the Writers’ Union in Romania and Romania’s General and Compared Literature Association. “In Eroticon, I attempted to reconnect literature to its most fundamental meaning, according to which literature is a means of reinventing the world, of providing sheer delight, and in doing so I left structural, aesthetic or axiological commentaries in the background”, says literary critic Mihaela Ursa. The critic Alex Goldis emphasized that the volume was all the more surprising since almost nothing prepared us for a hedonistic essay on Western erotic fiction.

Speaking now is Mihaela Ursa: “I was happy to give up the literary theorist’s lofty aesthetic stance, in order to discover the equally interesting and relevant mechanisms of reading as identification, the mechanisms of reading for pleasure, of a reading pattern that I termed the pattern of retrieving literature as life, of reading as a form of experiencing literature.”

One doesn’t read erotic fiction as such, but rather watches it unfold: this is the tenet from which Mihaela Ursa’s “Eroticon” starts. From the Ancient Greek novel to Anais Nin, Marquez, Nabokov, Bruckner or Beigbeder, things have not changed as much as we might think they have. To use the title of the book, the “Eroticon” entrusts literature, according to the author, with one of the powers specific to visual arts—that of conveying a whole story through one image alone—a nuclear scene, which is actually the core unit of classical erotic fiction. As Mihaela Ursa puts it, “My main concern is the extent to which erotic literature is significantly more at a risk of being read non-fictionally than other forms of literature. Erotic literature is taken as an existential model. We simply cannot cease to allow someone else to teach us how to be loved, and we believe the least credible of the teachers: literary characters.” Is that a big risk, we asked her?

Mihaela Ursa: “I think there is a huge amount of risk, and I noticed that when teaching my courses. Because, although in each of my lectures I make sure I specify that it is literature and not life that makes the topic of our discussion, many of the students I have been working with on those texts and who in turn are exemplary readers, cannot help experiencing that kind of slip, cannot help falling into that trap of viewing erotic literature contexts as some sort of model contexts, as models that they may follow in their everyday life.”

Mihaela Ursa confesses that, in the second part of the book, she let herself persuaded by the utopic ambition of capturing the impossible, of defining erotic fiction. And it is the author herself who offers a possible definition: “erotic fiction always provides an erotology, a pseudo-explanation, a pseudo-theory or ideology of love, an identification code of true love, or of the nature of love.”

Nora Iuga is viewed as one of the most notable prose writers in Romanian literature. She made her début in the 1960s, getting more than twenty volumes of poetry, fiction or diary published. For her literary achievements, Nora Iuga has been awarded the most notable literary distinctions in Romania. Her books have been translated and published in Germany, France, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Bulgaria and Slovenia. In 2007 Nora Iuga was the recipient of the Friedrich Gundolf Prize, awarded by the Deutsche Akademie fur Sprache und Dichtung, a distinction that usually goes to those who contribute to the dissemination of German culture around the world. Nora Iuga translated lots of books, by August Strindberg, ETA Hoffman, Friedrich Nietzsche, Knut Hamsun, Elfriede Jelinek, Herta Muller, Ernst Junger, Oskar Pastior, Gunter Grass, Aglaja Veteranyi, Rolf Bossert.

“The Sky Market. A Kitchen Diary” was first published in 1986. It is Nora Iuga’s most audacious books, and quite surprisingly, one of her least known volumes. Claudiu Kormartin wrote the foreword of the volume, which was brought out by the Max Blecher Publishers. He emphasized that “when it was first released, the book did not get the attention it deserved. We could say the literary formula the author resorted to was a bit too exotic.” Actually, the initial title of the volume “A Kitchen Diary” was thought provoking enough for the censorship to rule it out.

Speaking now is Nora Iuga: “It is the book from which censorship took out the biggest number of pages, and there is something special about this revised version, which might be of interest to everybody. I lent the original version of the book to the poet Mariana Marin, who was a very good friend of mine. Of course, books were brought out in the formula the censorship wanted, with our words replaced or deleted, but when we gave our writings to our friends, they read them in the original version. The book had been going through such a process the first time it was published, but my editor, Claudiu Komartin, found a very interesting formula. He placed the word I had originally chosen above the word the censors opted for. So here we are, many years later, with the book being reprinted with the words of the censors deleted and replaced with the initial ones.”

“Several worlds meet in the modest perimeter of the kitchen, where the poet’s existence unfolds as a pattern of overlapping experiences. Staunchly prosaic and sharply cruel, Nora Iuga’s poetry displays, at the same time, a rare audacity of the inspiration,” literary critic Valeriu Cristea wrote when the volume was first published.

Speaking again is Nora Iuga: “The book is special in various respects. It is the first book where I applied a principle of writing, actually of a kind of writing which is different from what had been in fashion in Romanian literature before, namely that of the total book where the writer, going from one state to the other, adapts his voice as well. Under these circumstances, chances are that literary genres change as well…In the prose fragments I often depict episodes taking place in the kitchen, but when states become more lyrical, the voice of poetry is heard.”

We end with an excerpt from “The Sky Market. A Kitchen Diary”: “Will I ever have the time to declare everything before that tribunal which looks at me with suspicion? Will I ever have the courage to go over my own censorship and say everything that ought not to be heard? Do I have the right to speak my mind, when offered the chance to keep silent? Members of the jury, we do not speak the same language. Have you ever lived the heroism, the madness, the risks of freedom?”